What Preschool Drop-off and Strategic Memos have in common

Yesterday, I received a text from my one-year-old son’s teacher. “We’re giving Asher so many hugs. He’s still crying for you, but at the playground he crawled up the structure, throughout the tunnel and down the steps, showing us all the things he is able to do. Slowly but surely he will get there! How are you doing? What’s one example of progress you’ve noticed this week?”

Before Franklin Street, I worked in the early childhood education field surrounded by veteran pre-k teachers, social workers, and people who nerd out over Dr. Montessori and Dr. Becky alike. Theoretically, I ought to know something about separation anxiety and strategies to ease kids into transitions.

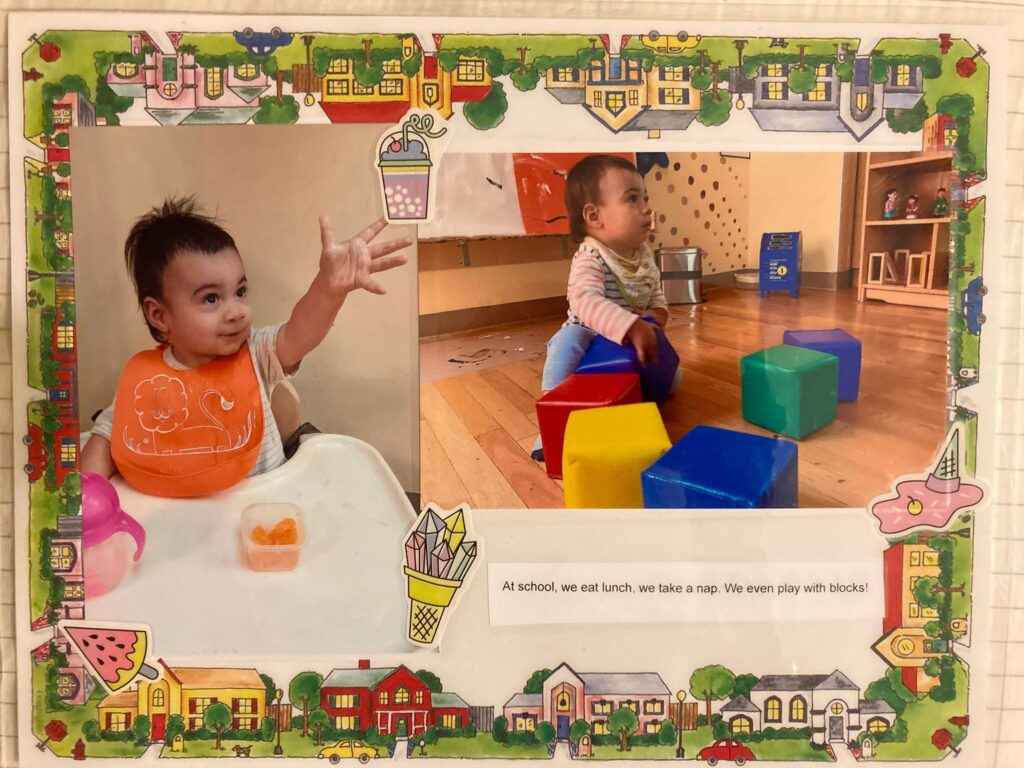

This is the reality: since Asher started daycare this fall, I’ve barraged my former colleagues with questions and gotten seriously useful advice. For example, they encouraged me to create a “social story” for Asher, illustrating his journey to school. I’ve shown up at drop-off wagging a rubber banana in hopes that a prop might distract Asher (he goes wild for real “nanas”). This tactic, by the way, majorly flopped, leaving me to look like a mom clown in front of fellow parents who give me those too-sympathetic eyes as I walk the long block away from my howling son.

All of these measures – the social story, the banana, a million other tips – are what leadership gurus like Ron Heifetz call “technical” responses to bigger, “adaptive” problems.1 The adaptive challenge, in this scenario, is adjusting to a big, world-rocking change (daycare). And you guessed it: the adapter-in-need isn’t so much Asher. It’s me.

Despite being a second-time parent and early childhood professional, I can’t help but wonder: is this a reflection of my parenting? Am I destined to endure a lifetime of soul-wrenching drop-offs? Will this ever get better?? This mode is, what my wife would call, Yvonne’s special brand of catastrophizing.

___

“How are you doing?” Asher’s teacher gently asks me. There it is, that classic pre-k teacher move: make me label my feelings. I scroll through my archive of texts to remind myself how I’m feeling.

Friend 1: How are you?

Me: ASHER’S FIRST WEEKS AT SCHOOL ARE A TOTAL DISASTER.

Friend 2: How’s your Tuesday?

Me: Ommmmmmgggggg, Asher crying all day. Nonstop.

Friend 3: What’s Asher’s status?

Me: No napping AT ALL. It’s never going to happen. All the work we did to sleep-train down the toilet.

This exercise punctuates the obvious: I’m a world-class worry-wart.

After a deep breath, I remember Asher’s teacher’s second question: “What is one example of progress you’re noticing this week?” This nudge is crafty, because it forces me to look for bright spots. So, I start thinking. Well, yesterday Asher finished his whole lunch at school – a sign, perhaps, of increasing comfort? The day before he stopped crying as soon as he entered his classroom – a sign of gradual acclimation? This morning he smiled (once) when he saw his teacher – a sign of a developing relationship?

I see what’s going on here! If I notice small victories, I can temper my anxiety. If I can temper my anxiety, Asher thinks that mom is cool, calm, and collected, and he stays steady.

Dare I say it? Asher’s teacher may have just coached me out of my short-term panic into acceptance that this is bound to be a long game.

When I was a kid, I associated the word “coach” primarily with my high school basketball coach who once opened the team van door in the middle of the Westside Highway to invite me to “exit” if I had another thing to say about the game plan she had drawn up. Later in grad school, I read a lot about the theoretical promise of coaching but didn’t practice it enough to understand its true potential. It wasn’t until I landed in the NYC Department of Education where stress was high and change was rampant that I understood how transformative coaching could be.

At the DOE, I was running a big team tasked with providing mental health services in pre-k programs across the largest school district in the country. The work felt non-stop and constantly in flux. Every Wednesday, my colleague Remi and I hunkered down beneath a back staircase. We’d start with a quick check-in: what’s your energy on a scale of 1-5 today? (It was usually 1). And then we’d dig into the challenge du jour.

I’d hold forth about the latest issue I was having with an intransigent direct report. Remi would listen, reflect back what she heard, and ask me to clarify as I constructed stories about my supervisee’s behavior. “What is at stake for them?” she’d ask, pushing me to contemplate someone else’s perspective. “What intentions are you ascribing to their behavior?” With each question, I landed on a new, or at least deeper, understanding of the situation. Remi often closed with a challenge: “What’s one small action you can commit to taking immediately?” Then, we’d switch roles. These “coaching” conversations became my lifeline in otherwise turbulent waters.

Over time, I found myself drawing on the skills developed in these sessions with Remi in all sorts of contexts. I started to kick off every meeting I facilitated with a simple question: “What has your attention right now?” The range of responses – from stories about childcare fiascos at home, to confessions about stressors at work – not only opened up space for vulnerability, but helped me approach the conversation with empathy and context.

I remember a high-stakes retreat in which a group of seasoned leaders swirled about how to frame a point in a memo. I chimed in with some apprehension: “What’s the risk to the team if we just share the current draft as is?” My colleague replied: “Well, if we’re not perfectly precise we open ourselves up to gross misinterpretation.”

Ah, this isn’t at all about language, I thought to myself. “Got it,” I said aloud. “You’re worried that misinterpretation might jeopardize the trust you’ve been working so hard to build with this partner. What, specifically, do you fear might be misinterpreted?” My colleague paused before offering a well-considered response. And so on, and so on.

With each answer, I’d summarize what I heard and then ask another question. Together, we got closer to the root of the “stuckness,” extracting ourselves from the spinning on words and redirecting our energy to the central issue of trust. I began to see a coaching opportunity in every interaction I had at work no matter what my role or formal authority was.

___

At Franklin Street, we believe that everyone can be a coach, and everyone needs a coach. When we enter into explicit coaching relationships with our clients, we start by aligning on goals. Then, we interrogate and reflect on problems together, taking stock of progress along the way. We notice our behavioral defaults (yup, you’re doing that thing again) and go-to mindsets (you’re thinking that way again). And together, we create a space of trust in which we can study our own motions in the working world without the pressures of Slack messages and Zoom chats dividing our attention. We believe this space is critical for people to ultimately grow.

Coaching isn’t limited to a bounded 1:1 relationship. We take a coaching posture in everything we do, because all good work requires vulnerable leadership. As a client recently said about our approach, we are equal parts supportive and “boundary-pushing”. We help our partners unravel complicated stories to get to the root of the problems that they really want to – and can – solve.

A week has passed since I started writing this blog. Asher had a couple setbacks at school. Today, no morning nap, a lunchbox returned with oozing, sallow pieces of ‘nana smushed into the crevices of each bento compartment. And so, my phone buzzes: “There will be good days and bad days,” Asher’s teacher writes. “Today, Asher took 5 steps forward, fell down, and got back up on his own.” I couldn’t have come up with a better metaphor myself.